As religious minorities expand and diversify through ongoing transnational migration, a “new religious heritage” is gradually emerging across Europe (Knott, 2010). Unlike traditional expressions of European religiosity, which are often rooted in monumental architecture, this new heritage takes shape in modest, improvised settings. Migrant communities are establishing spaces of worship in repurposed urban environments—former theatres, garages, commercial premises, private residences, and even the basements of apartment buildings (Lefebvre, 2020). These often hidden spaces reflect the dynamic ways in which migrants negotiate their presence within cities, carving out places of belonging and spirituality while adapting to new cultural and legal landscapes.

More Info

However, this phenomenon brings significant challenges. As Astor and Griera (2016: 250) argue, the diversification of Europe’s religious landscape has intensified debates over recognition, visibility, and accommodation. Many of these worship spaces remain invisible to the wider public, a visibility gap that reflects deeper structural inequalities and contested notions of pluralism (Cesari, 2004; Barbier, 2020). Several factors contribute to this concealment: limited financial resources often prevent the construction of purpose-built religious buildings, while restrictive zoning laws and legal frameworks make obtaining permits difficult. These obstacles are further compounded by societal marginalisation and, in some cases, overt hostility toward minority religious groups (Bowen, 2007; Fetzer, 2016).

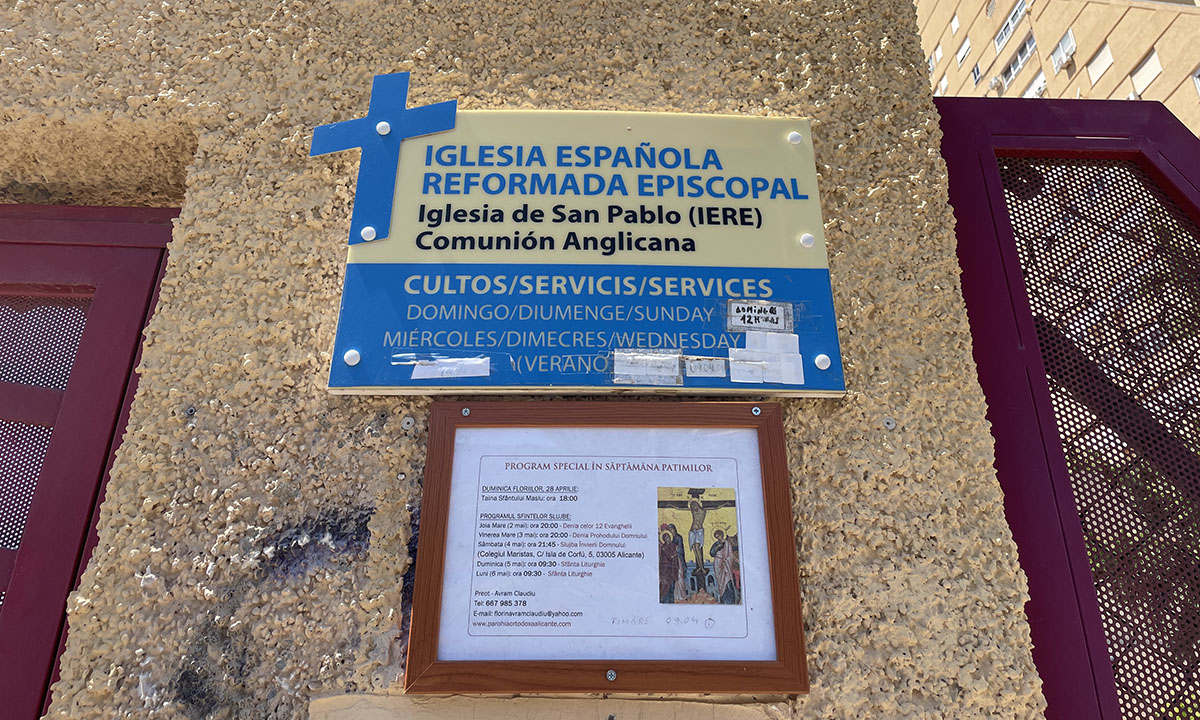

Initial fieldwork in Alicante illustrates how these dynamics play out on the ground. In many neighbourhoods, places of worship operate without external signage or public identifiers, making them virtually invisible to passersby. This was particularly evident among Evangelical congregations—composed largely of the local Roma population alongside Latin American migrants—as well as Muslim communities from North Africa and Orthodox Christian groups, especially Romanian Orthodox believers. Despite their discreet external appearance, these spaces function as vibrant hubs of social and spiritual life, sustaining religious practice, cultural traditions, and networks of mutual support (Griera & Martínez-Ariño, 2018).

The decision to remain hidden, in numerous cases, reflects fears of rejection from the host society. While active Catholic religious practice in Spain has declined in recent decades, Catholicism continues to exert significant cultural influence, shaping the boundaries of acceptable public religious expression (Knott, 2016). For minority communities, maintaining a low profile can therefore be a pragmatic response to the challenges of integration and recognition (Cesari, 2013).